A Stroll Down Memory Lane

What follows isn’t so much a story as it is a series of stories, or memories, of my time on the DEWLine. The stories are all of a personal nature and hopefully put a human face to a potentially highly technical topic. For the most part, the stories follow a general time-line from when I first arrived in the Arctic in 1960 until I left for the last time three years later in 1963.

You can either start at “The Arctic Adventure Begins” and work your way through the stories and adventures as the are presented or you click on any of the links below to get to a specific adventure.

INDEX (of sorts)

- The Arctic Adventure Begins

- A Barren Land

- Auxiliary (Aux) Sites

- First Assignment: CAM-4, Pelly Bay NWT

- Land of the Midnight Sun

- The Fishing Expedition

- Saturday Night in the Arctic

- Movie Time

- Christmas at the Real Pelly Bay

- Christmas at CAM Four

- Christmas Menu

- Drag Racing

- The Case of the Missing Scotch

- Missed Boogie (Target)

- Working in the Dark

- The Haircut

- No Days Off

- This is Santa Claus Calling

- A Woman’s Voice

- Escape from the North

- Not Much Pay

- Being Bushy

- Returning North

- Time to Move On

- Working Around the Clock

- Lesson Learned

- Doctor Brian

- The Dancing Washing Machine

- King of the Northwest Mounted Police

- No Rest for the Wicked

- Now That’s Cold!

- A Time Management Lesson

- Time to Move Along Again

- Here We Go Again

- Movie Time

- God’s Will

- The BOPSR Club

- Another Kind of Freezing

- Going Crazy

- The Ghost at the Airfield

- Idle Hands (and Minds) at Work

- The Top of the Mountain

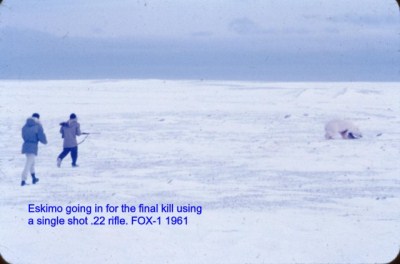

- Polar Bear Hunt

- Foxes, Foxes, Everywhere

- Becoming an Old Hand

- One Last Time

- Home Again

- More Scientific Experiments

- The Cuban Missile Crisis

- Talking to SAC’s B-52’s

- Tactical Call Signs

- Dealing with Death

- A Movie to Remember

- All Good Things Must Come to an End

The Arctic Adventure Begins

So, in July 1960 at the tender age of 19, I found myself near the top of the world above the Arctic Circle as a civilian radar technician (Radician) on the Distant Early Warning Radar Line (DEWLine), ready to stand watch over the North American continent, ready to sound the alarm in case of attack by the Soviet Union. It was all very exciting for a young man.

Back to Index

A Barren Land

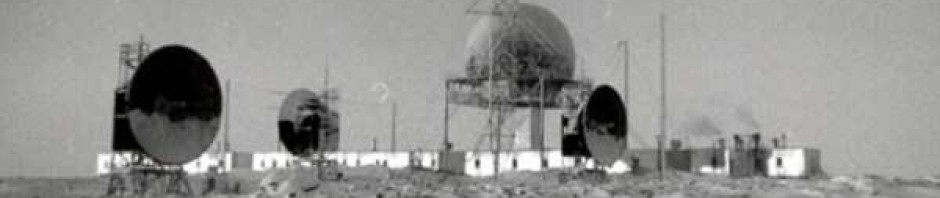

I remember being tired and excited when we landed at Hall Beach, also known as Fox Main. The airstrip was about a mile and a half from the main buildings and you could easily see the huge white radome in the distance.

We all piled into the blue US Air Force bus for the trip to the main site. In addition to us newbies, there was a fair number of people who were returning from R & R (rest & recreation) leave, as well as some long-timers who were returning on a second or third contract.

I don’t remember much about those first few days apart from quietly celebrating my 20th birthday on August 4, 1960, at Hall Beach, high above the Arctic Circle.

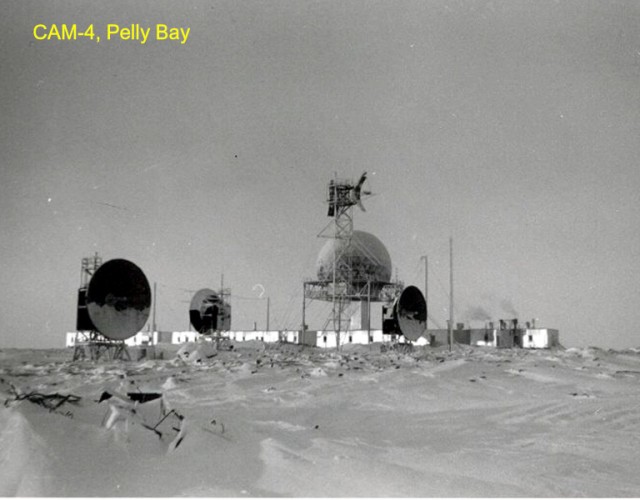

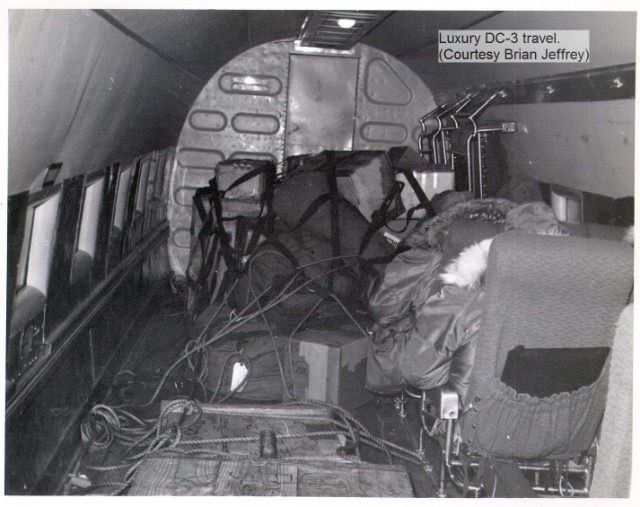

I was assigned to the auxiliary station (AUX-site) at Pelly Bay, code-named CAM Four, and was awaiting transport for several days. Finally the day came, and I was thrown into a DC-3 along with a few sacks of mail and some movies for the two-hour lateral flight to CAM Four.

Back to Index

Auxiliary (Aux) Sites

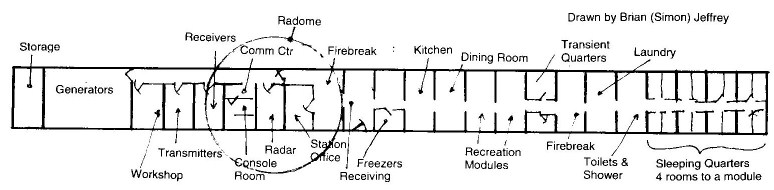

The typical Aux-site was made up of series of 25- by 16-foot buildings called modules, connected together side-by-side. The end result was a “module train” that was 25 feet wide by about 385 feet long.

I only have a vague recollection as to the layout; however, I was able to find the following description by Clive Beckmann on the Internet.

- Module 1: Storage area

- Modules 2 – 4: Diesel generators for power generation and hot water for heating

- Module 5: Electronics workshop and power mechanics office

- Module 6: Transmitter Room

- Module 7: Receiver Room

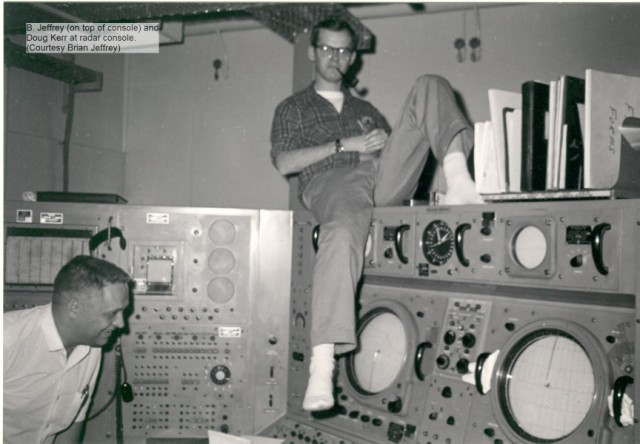

- Module 8: Surveillance Room (Radar Console) and Communication Centre

- Module 9: Radar Room

- Module 10: Station Offices

- Module 11: Firebreak

- Module 12: Receiving Room for incoming goods

- Module 13: Walk-in Freezers and Incinerator Room

- Module 14: Kitchen

- Module 15: Dining Room

- Module 16: Recreation area where movies were shown

- Module 17: Recreation area containing pool table, bar and Emergency Radio Room

- Module 18: Transient Sleeping Quarters

- Module 19: Firebreak

- Module 20: Laundry Room, Darkroom, Potable water

- Module 21: Bathroom and Septic Tank

- Modules 22 – 25: Sleeping Quarters, 4 rooms to a module

The module trains were built on pilings that were driven into the tundra so that the whole building sat about four or five feet above the frozen land. The base of the radome that held the radar antennas was 50 feet above ground and located directly over the Radar Room module. The rigid radome itself was 25 feet in diameter and contained the two AN/FPS-19 antennas, mounted back-to-back.

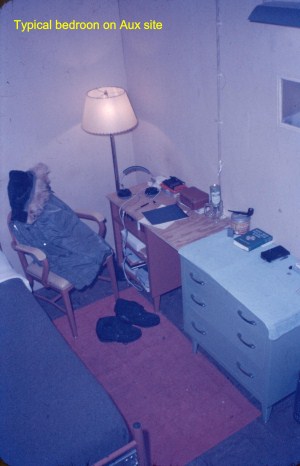

The facilities were spartan and utilitarian, yet comfortable. Those people who were stationed at a site on a ‘permanent’ basis were assigned an 8 by 10 bedroom that contained a bed (of course!), a dresser, chair, a night table/writing desk, lamp, and small closet to store your gear. Transient personnel, people who were visiting or passing through the station, would be housed in the Transient Quarters where there were three double bunks and not much else. The site has a communal washroom that held a toilet, wash sink, and a shower. The laundry area had a washer and dryer along with an iron and ironing board for the fastidious.

In addition to the main module train, each Aux-site had a garage and warehouse. There were usually a number of abandoned Jamesway huts (long, half-round tents with a rigid frame and a canvas cover) that were left behind from the construction years. During the summer months, these tents could be used to house the extra workers that arrived each spring to do major outside work on the site.

Depending upon the time of year, an Aux-site had a complement of between 12 and 40 people. There were some ten to 15 in the winter months and more during the summer when construction and outside repairs were being done. Of the complement, seven to nine were radicians, if we were lucky.

By lucky, I meant that we didn’t always have our full complement of radicians which meant extra work, long hours, and no days off. In one case we went undermanned for several months. People tend to get cranky after several months of no time off, but the job came first.

Back to Index

First Assignment: CAM-4, Pelly Bay NWT

Upon my arrival, I was treated as the outsider I was until I was befriended by one of the other radicians by the name of Tom Billowich. It appears that no one on the station cared much for Tom, and I became his only friend. I suspect he glommed onto me when I first arrived so that he could reserve me as his personal friend.

I learned later to be wary of people on the DEWLine who were looking for instant friendships. They seemed to come fully equipped with a number of quirks that caused people to want to keep them at arm’s length.

However, for whatever reason, Tom and I got on fairly well together and I had a number of adventures with him, the last of which was a misadventure and saw Tom leave the DEWLine for the last time.

Rudy Hubner was CAM Four’s station chief. He was a fine gentleman and went on to become station chief at Fox Main where our paths would cross again. The lead radician was a short fellow by the name of Gaetan Chapeau, who always seemed to have a chip on his shoulder. We used to call him Napoleon behind his back.

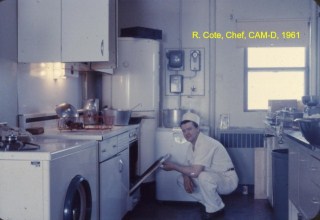

The chef was a crazy Frenchman by the name of Red Chenil. Our paths were destined to cross a number of times during the three years I was on the DEWLine. He was an excellent chef, if a bit strange. He used to jokingly threaten me with a butcher knife from time to time. I think he’d been up north a bit too long.

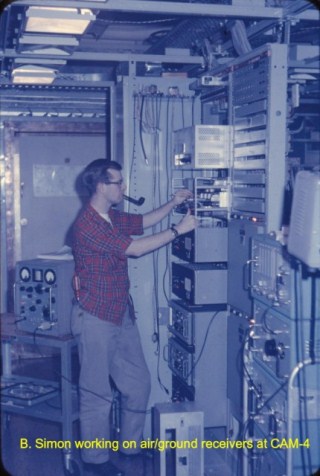

So, CAM Four was where I cut my teeth on the DEWLine. Because I was a bit of a technical nerd, I was keen on learning everything I could about the equipment at the station. Although we were capable of looking after all the electronic gear, we were often assigned to specific types. I was assigned to look after the air/ground and vehicular radios as my specialty. I was also responsible for maintaining the radio system that was used to communicate with the Intermediate stations (I-Sites) on each side of our site.

There were two Collins VHF air/ground radios systems, consisting of a 242F3 transmitter and 51N2B receiver, one for the general aviation frequency of 122.2 Mhz and one for the emergency frequency, 121.5 Mhz. These radios were used primarily for communicating with civilian aircraft. We also had two UHF air/ground radios systems, consisting of an AN/GRT-3 transmitter and AN/URR-35 receiver, for communicating with military and SAC aircraft on 236.6 Mhz as well as monitoring the military emergency frequency of 243 Mhz.

The radio system that was used to communicate with the two I-sites was a General Electric model VO-38 VHF system which ran about 250 watts, as I recall.

The GE VO-38’s were also used as the base unit for communicating with the Main and Aux station’s vehicular radios, AN/VRC-19. This meant that whenever the console operator called one of the station’s mobiles, the people at the I-site, some 50 miles away, were party to the conversation, or at least half of the conversation. This could be quite an aggravation at the I-site when it happened in the middle of the night and you were trying to get your beauty sleep.

I was also responsible for the LF beacon which was a Wilcox 99C also known as the AN/FRT-37.

Each station was equipped with an Emergency Radio Room containing a Collins 431B1 1000 watt transmitter, 51J-4 receiver, and a three element bean antenna. This room was at the opposite end of the module train from the main electronic modules so that in case of fire, it might be spared and used to summons help.

Federal Electric had a training program where a radician could take technical exams on the various pieces of equipment. There were five levels of proficiency with a Level 5 (called a Five-level) being the best. I quickly became a Five-level on the equipment for which I was responsible. Being a bit of a technical nerd, as I mentioned earlier, coupled with the fact that we didn’t have a lot of things to keep us busy, gave me the time to delve in-depth into the various pieces of electronic equipment we were responsible for. By the time I left the DEWLine in 1963, I had attained a Level 5 proficiency in five different equipment categories, something that had never been done up to that time.

Back to Index

Land of the Midnight Sun

For most of the summer months in the high Arctic, the sun never sets. It just dips and touches the horizon around midnight before rising up high into the sky again. Hence the phrase, the land of the midnight sun.

This causes some interesting challenges, one being a difficulty in telling day from night. When it’s as bright out at 3AM as it is at 3 PM, how do you tell the difference? You can’t really and sometimes you got them confused. Your work becomes your time regulator.

Unless you had a clock that told 24 hour time instead of the usual 12 hour clock, it was easy to confuse morning with afternoon, day with night, unless you learned how to read the sun’s position in the sky.

It also played havoc with sleeping habits, especially for those people who are used to waking when dark turns to light.

I found it almost impossible to sleep with light pouring in through my bedroom window so I found a spare blanket that I nailed over my window for the summer months,

Then as the year wore on, the days would get shorter and shorter until you were pretty well in total darkness. You could tell it was noon when the horizon got a lighter shade of dark as the sun rose to its peak but still remained below the horizon.

Once again, there was no visible difference between 3 AM and 3 PM and only a slight difference between 12 midnight and 12 noon when it got slightly less dark. On cloudy days, you simply wouldn’t be able to tell the difference between noon and midnight

Living and working in constant darkness can take its mental toll. It’s no wonder, that in Scandinavian countries, the suicide rate increases dramatically over the winter months.

Seasonal differences had a greater impact on those people whose work took them outside. For technical people, we were either sitting in a darkened room watching the radar at the console or in well lit equipment rooms keeping the electronic gear humming.

It’s too bad we weren’t supplied with 24 hour wristwatches.

Back to Index

The Fishing Expedition

I mentioned earlier that I had a number of adventures with Tom. I call one of these adventures the fishing expedition.

It was one of those rare days off that we occasionally got, and Tom convinced me that we should walk the six miles down to the airstrip and do some fishing for Arctic char. Our chef, Red Chenil, would have been delighted to cook up anything we caught for us and if there was any left over, we could share it with some of the station members.

Six miles is a bit of a hike, so when I protested the long walk, Tom said we could take a shortcut via the old road. Besides, the people at the airstrip could give us a drive back, Tom said. So we got the station’s fishing gear and off we went.

We were about halfway to the airstrip via the old road when I noticed the people driving up the main road back to the station. So much for our ride back… I was starting to be an unhappy camper.

We finally got to the lake by the airstrip. Tom was the first to cast his line. It went out about 15 feet and came to an abrupt stop. That was all the line he had on his reel. Hardly long enough to reach the water. No problem. I still had my rod and reel and it looked pretty full.

I’m not a fisherman, but being game to try things, I cast my line with all the vigour I’d seen other fisherman display. Out the line went…and then it just kept on going. No one had attached it to the reel! Both Tom and I watched as my hook, line and sinker went flying out over the lake to disappear forever.

The Arctic char were safe for a while longer. It was a long, quiet, six-mile, uphill hike back to the station. I didn’t talk to Tom for a few days and I’ve never been fishing since.

Back to Index

Saturday Night in the Arctic

Officially, we weren’t supposed to have any hard liquor on the sites. Every spring, the sealift and airlift would bring up large quantities of beer for general consumption. We were allowed to purchase six cans of beer a week. I didn’t care much for beer, and still don’t, so I’d sell my six cans off to the highest bidder. I never got rich, but it gave me spending money for other sundries.

In any event, despite the supposed lack of booze on the sites, each station had a well-stocked bar. Whenever anyone when south for their R&R leave (a two-week rest and recreation vacation), they were tasked with returning with a suitably large quantity of booze. Other bottles came by mail, some inside loaves of bread, many just well packed as gifts for the long journey. Basically, Saturday night was escape night and some people escaped farther than others. One such escapee was a radician by the name of Brian Webb.

Typical Aux station lounge area. This one was at FOX-2. Notice the fox and the two glasses on the bar. Also note the ample supply of booze!

Brian Webb didn’t just like to drink, he liked to get smashed. This didn’t usually cause a problem except on Saturday night, or more importantly, on a specific Sunday morning when he was supposed to relieve me from my radician duties.

It was a typical Saturday evening at CAM Four and the station personnel were gathered in the recreation module areas enjoying a few drinks and games of pool and cards. I had to go on duty at midnight, so I was drinking pop while most of the others, including Brian, imbibed the devil’s brew.

The evening festivities carried on well after I went on shift at midnight, and every now and then I dropped down to the recreation module to see how things were going. What wasn’t going was Brian. He wasn’t going to bed. I mentioned to him that he was to relieve me in a few hours and he might want to get some sleep. My pleas fell on deaf ears and a sodden mind. I was getting annoyed.

On one of my trips to the recreation area, I carried on to my sleeping quarters, which were across from Brian’s. I have no idea what possessed me to do what I did next. I got a tube of shaving cream from my room, went across to Brian’s room, found his toothpaste and carefully transferred a slug of shaving cream from my tube into his toothpaste tube, after which I went chuckling back to work.

Eight o’clock in the morning came, but Brian didn’t. Nine passed, then ten. Finally, at around 11 a.m., a bleary-eyed, dishevelled, somewhat-still-drunk Brian appeared. As he mumbled a good morning into my face, I caught the smell of booze, bad breath…and shaving cream. I asked him if he had shaved his teeth that morning. He looked at me quizzically, mumbled something, and plopped himself down in front of the radar console. I went off to bed.

It was later in the day when the final act of the play happened. I was sitting in the toilet when a now-sober Brian appeared holding his toothbrush and tube of toothpaste. Oh no, I thought. This can’t be happening before my eyes as I strained to see through the crack of the toilet door. It was, it was. He was going to brush his teeth!

It only took a few seconds, but now that he was sober, Brian could actually taste the shaving cream. It wasn’t a pretty sight, so I’ll spare you. I enjoyed every minute of it.

Of course, Brian accused me of putting shaving cream into his toothpaste tube, but I denied any knowledge of it. In the end, he was never sure enough to take revenge on me.

But I was very careful about where I hid my own toothpaste until I left the site.

Back to Index

Movie Time

Saturday was usually movie time, as well. When the weather cooperated, we’d receive three movies a week on the weekly lateral flight that also brought us our supplies and, more importantly, our mail.

The movies were shown in the recreation module, using a 16mm projector. Each film usually had three reels, and we’d have to stop between reels to refill our drinks while the projectionist set up the next reel for viewing. As technical experts, in addition to maintaining the projector, the radicians were also charged with being the projectionists.

As a general rule, we got first-run movies and were well received by the station staff. Not all the movies were good and that usually got people shouting and throwing things as the evening wore on. I remember one dog of a movie, Carthage in Flames, which was so bad that we all had problems following the storyline. Characters on the screen would race their chariots from the right to the left and then back again, over and over. It was so confusing that at the end of the first reel, when the projectionist missed the second reel and put on the third one, no one knew until the closing “The End” appeared on the screen. At first we all thought it was just a (thankfully) short movie. We didn’t understand the movie anyway and only discovered the un-played second reel as we were packing up this dog for shipment to the next site.

I often worked the evening or night shifts as I enjoyed the relative quiet of the station during those hours. After I got off the evening shift one Saturday I decided to watch a movie on my own. It was about 2 a.m. My shift-mate had gone to bed and all the rest of the station was sleeping, except for the two other radicians who were working the overnight 12 to 8 shift.

The movie was Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho. I didn’t know who Hitchcock was or that he made horror/thriller movies, so I was blithely watching along what I thought was a mystery movie when I got to the part where Janet Leigh is in the shower at the Bates Hotel, semi-naked (which really caught my interest), when all of a sudden the shower curtains get pulled away and there is Anthony Perkins slashing away at Janet Leigh with a huge knife. Blood was spurting everywhere. It was at this point that the reel ended. There I was, absolutely horror-struck, sitting in a darkened room, alone, thinking, what the hell was that?

I’ll tell you, that movie had a profound impact on me. I don’t think I took a shower for months, and when I did, it was during the day. Colour me young and impressionable.

Back to Index

Christmas at the Real Pelly Bay

Father Vandeveld had been in the Arctic longer than I had been alive. This venerable gentleman had spent over twenty years in the Arctic, most of them at the Pelly Bay Mission. He was to give me one of my most memorable Christmases ever.

CAM Four, Pelly Bay, is located about ten to 12 miles north of the Pelly Bay Mission that Father Vanderveld called home. You could always tell when people from the Mission visited the station because they only had to be in the building for a few moments before the air circulating system alerted us that either the Eskimos from the Mission had arrived or someone had left a dead seal in the entranceway.

Note: While I refer to “Eskimos” in this document, the politically correct term for the indigenous people of the North is “Inuit.” I’ll continue to use the term Eskimo as that was what I knew them as. Of course, they are fine people and I mean no disrespect.

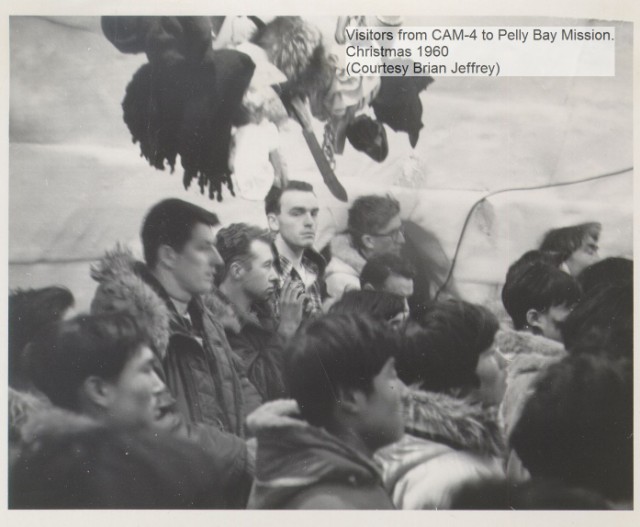

One such visit brought with it an invitation to visit the Mission on Christmas Eve to join in the festivities. A group of eight or ten of us accepted, and on the appointed day we all climbed into the Bombardier snowmobile (Snow Pig) and drove to the Mission.

There were approximately 120 Eskimos living in and around the Mission at that time. What they had done in preparation for the occasion was to build four fairly large igloos in a square, placing them some 30 feet from each other. They then built a huge igloo using the four smaller ones as corner pieces. They completed the structure by removing the now interior walls of the four small igloos, leaving a huge 50-foot round igloo with four small alcoves.

All 120 inhabitants of the Mission were in the igloo that evening. A mass of humanity for Christmas Mass. They sang and played games. They had a piñata-like object hanging from

the top of the structure, and all the Eskimo children had an opportunity to be blindfolded and to try smacking it with a stick. When one of the children did finally hit it, all manner of treats rained down on the spectators.

As strangers and visitors, the people from CAM Four stayed in the background, observing and enjoying the simple pleasures of the event. It was a touching and moving experience.

On the return journey to the station in the snowmobile, one of the Eskimos offered me a frozen “treat.” I thanked him, and as I munched on the treat and it began to thaw in my mouth, I realized that it was a piece of raw frozen fish. I don’t like raw fish.

To this day, I’m not a big fan of sushi (raw fish), but whenever I have the opportunity to taste some, I’m transported back to that quiet evening many years ago and remember Christmas at the real Pelly Bay.

Back to Index

Christmas at CAM Four

After the Christmas Eve at the Pelly Bay Mission, the Christmas dinner at the station was a less emotional affair. To the company’s credit, they really tried to give us a bit of a Christmas feast. They had formal menus printed up, and the chef prepared special fare for the occasion. It was a very pleasant evening, and everyone partook of the meal, including the on-shift radician who was supposed to be doing maintenance duties.

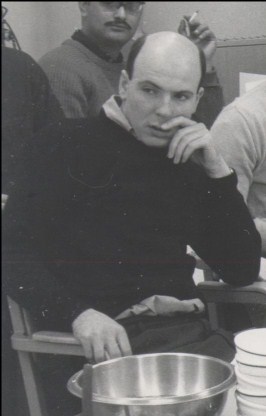

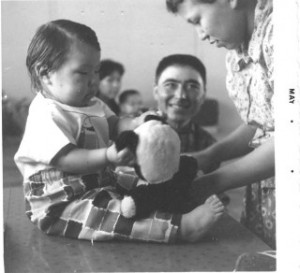

Christmas dinner at CAM-4, 1960. I’m in the front, second from the right, wearing a short-sleeved white shirt. This is entire complement of the station less the chef, who took the picture, and the radician on duty at the console.

Back to Index

Christmas Menu

Back to Index

Drag Racing

Entertainment opportunities 120 miles inside the Arctic Circle are few, so when I had a chance to learn a new “trade,” I leapt at the opportunity.

In order to keep our airstrip useable, it wasn’t ploughed, it was dragged. We would tie a huge log or bar about 20 feet long and drag it crossways up and down the airstrip using a D-8 Caterpillar.

In one of my bouts of boredom, I got the lead mechanic to show me how to drive the D-8 and drag the strip. If I thought my job was boring, this was the pinnacle of boredom and the mechanic was delighted to suck me into doing this mindless job.

I found it mildly interesting for the first couple of hours, after which it just became hard work. The actual driving up or down the strip wasn’t such a big deal, but getting the beast of a D-8 turned around without fouling the trailing log was a challenge.

So while it wasn’t exactly drag racing, dragging the strip helped pass the time and served a useful purpose. If we didn’t keep the strip in good condition, we wouldn’t be receiving any aircraft. No aircraft meant no movies and, more importantly, no mail. In the end, I didn’t exactly consider myself a heavy equipment operator. I only did it once. Too much fun isn’t good for a person.

Back to Index

The Case of the Missing Scotch

Some people shared their booze with others willingly, while others shared less willingly or even unknowingly. Here’s what happened to Albert’s scotch.

I don’t know why Albert Lemaire coveted his bottle of scotch, but he did. It was as though it was an Aztec treasure to be displayed and talked about but never to be touched by others. If Albert had simply kept his mouth shut, he might have had a chance to enjoy his scotch.

Albert was a sector electrician and travelled from site to site doing esoteric electrical repairs that the station mechanics didn’t or wouldn’t do. He’d been at CAM Four about ten days and no amount of cajoling or convincing could get him to share the pleasures of the bottle’s contents. We tried buying it off him but to no avail.

It was early on an uneventful Saturday when a dastardly plot was hatched. Albert was due to leave the next day and was down at the airstrip doing his electrician thing when some of the station crew decided to liberate the scotch. We weren’t going to steal it; we were going to borrow it.

We found the bottle tucked away in Albert’s bunk, and using a razor blade, we carefully cut the seal around the screw top. We then transferred the contents to another bottle and refilled Albert’s bottle with a scotch-looking fluid made of tea. As a final touch, we resealed the top, using some clear scotch tape so the bottle would crack as it was “opened” sometime in the future.

That Saturday evening when we were all sitting around the bar/lounge area, one of the guys “discovered” some scotch behind the bar and offered it to everyone, Albert included. It was a grand evening. Everyone was getting pleasantly potted on Albert’s scotch, including Albert.

The next morning, some of us slightly the worse for wear saw Albert off as he crawled aboard the plane for the short hop to CAM D, the I-site to our west. We waved Albert and his bottle of tea goodbye and silently went back up to the station.

It was a couple of days later when the radio channel from CAM D came alive with some of the bluest language I’ve ever heard. Apparently, Albert had opened his bottle of scotch only to discover that tea doesn’t taste anything like scotch. We turned the volume down and let Albert rant.

If only Albert had kept quiet about his coveted scotch. Little did I know that I would be following Albert to CAM D in the near future.

Our primary mission wasn’t to visit, fish, watch movies, or play practical (and non-practical) jokes on one another. There was a much more sober side to our existence and we took it extremely seriously.

Back to Index

Missed Boogie (Target)

It was a quiet Arctic night. But then most Arctic nights on the DEWLine were quiet. Tom Billowich and I were halfway through the midnight to 8 a.m. shift. It was Tom’s turn to man the console, so I went off to do some preventative maintenance routines (PMs) on the air/ground transmitters in the transmitter room.

It was somewhere around 4:15 to 4:30 AM when all hell broke loose. We received a call from FOX Main to do an immediate Minimum Discernible Signal (MDS) test on both beams of our FPS-19 radar system. There was no mistaking the sense of urgency. I called the console and asked Tom what was up. “There’s something wrong with the radar,” he told me, “We missed a target.”

I hot-footed it to the radar room and did the tests. No problem. The radar was just fine. What was going on? I went back to the console room where Tom told me that both CAM Three and CAM Five on each side of us had reported the target but that we weren’t painting it. I looked at the right-hand screen of the console. We were sure as hell painting it now. What gives?

I asked Tom what was going on. All he would tell me is that we missed the bogie and he was now in deep doo-doo. He denied dozing off. I sent him off to do another MDS test for himself and he returned to confirm my earlier results. There was nothing wrong with the system. He really was in trouble.

There was a lot of mental and physical hand-wringing on Tom’s part as he continued to claim that he hadn’t fallen asleep and that there just had to be something temporarily wrong with the radar.

Before the end of the shift, we were informed that Tom should gather all his belongings up and be ready for pickup later in the day and taken to Fox Main.

Tom not only gathered up his things but gathered up his thoughts as well. By the time he was being driven to the airstrip for pickup by CF-IQD, he was prepared to present a vigorous defence in an attempt to salvage the situation and his job. I shook his hand and wished him well.

Tom never got an opportunity to present his case. They took him off the lateral flight and put him directly on the southbound flight, out of the Arctic, and out of a job.

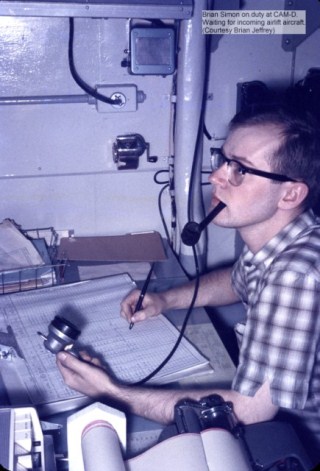

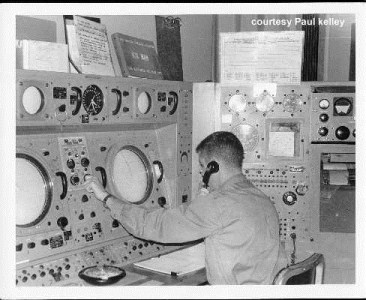

It was all right to be relaxed on duty as I was here but falling to sleep was the kiss of death and an absolute no-no.

Technical failure aside, there was simply no acceptable excuse for missing a target. Tom missed the bogie and, in the end, we missed Tom.

Back to Index

Working in the Dark

One of the things that helped seal Tom’s fate was the cameras that were mounted on the radar receivers in the radar room. As soon as a radar target triggers an alarm, the cameras are supposed to photograph one full sweep of the antennas. The system didn’t always work as advertised, but it did in Tom’s case and the resulting photo showed a target.

Each Aux and Main site had a fully equipped darkroom, and if you knew what you were doing, you had free use of all the supplies to develop your own films and photos. In fact, you could use the darkroom even if you didn’t know what you were doing, and that was the case in my situation.

At the time, no one at CAM Four was particularly interested in developing film or even learning how. Always up for a challenge, I volunteered to be the station’s resident darkroom specialist.

Before long I was mixing chemicals and developing my own black and white films, as well as printing as many photographs as I wanted. Ultimately, I even expanded my talents into developing colour slide film. I had to purchase the chemicals from the south as the stations were only equipped to deal with black and while film.

Still, it was a great way to learn darkroom techniques at absolutely no cost. Hell, I could use an 8 x 10 sheet of photographic paper just to do test shots!

Back to Index

The Haircut

I want you to leave the DEWLine for a moment and fast forward to the summer of 2009.

I was sitting in the barber’s chair having what little hair I have left trimmed when I asked Rosie, my barber, how long it takes to be trained as a barber. She told me that it takes about a year’s worth of training before trainees are let loose to work their magic amongst unsuspecting heads. Even then, the haircuts are free so people can’t complain about the results.

I pondered that gem of information as I let my mind rewind to some 48 years earlier to 1961 when I gave my first (and only) haircut.

As a general rule, the station chef was the person who cut hair, at least at CAM -4 it was. Our chef was a crazy French Canadian by the name of Red Chenil and who was a couple of knives short of a full set.

You knew that you were in Red’s good books when he picked up a butcher knife and threatened to kill you. For some reason, Red took a shine to me and often threatened to cut off various parts of my body. Maybe it was because I was always practising my French swear words on him.

In any event, Red also doubled as the station barber and did a real good job. As with any skilled practitioner, Red made cutting hair look relatively easy. I mean, if someone who specializes at hacking sides of beef apart with a butcher knife can cut hair, surely someone with my finely honed soldering skills can also cut hair. Or so I thought.

My opportunity to test out my hair cutting skills (or lack of same) came about quite innocently.

It was the summer of 1961 and CAM Four’s population had swollen by the addition of a construction crew who were working on the airstrip and other construction projects that could only be done in warm weather.

There weren’t enough sleeping quarters in the main building to house the newcomers and they had to bunk down in the old Atwell tents that were still on the site from the early construction days. Although housed away from the main building, they always had their meals with us in our dining module.

One evening I was sitting across from a young construction worker and we struck up a conversation during which he asked about how he could get his hair cut. Being adventuresome, I ventured that I could do it for him. I managed to avoid answering any questions about my barbering experience until later, when it was too late. We agreed to meet later that evening in the laundry area which doubled as the barber shop.

Everything went along fairly well, in that I was able to seriously reduce the amount of hair the fellow had on his head. It was the finishing touches that caused the problems.

The best way to explain what went wrong is to use the analogy of trying to level a wobbly dining table. First you cut a bit off one leg and test it out. It’s still wobbly but in a different direction now, so off comes a bit of another leg. You keep repeating the process of taking a bit off one leg after another until eventually you end up with a coffee table that is, unfortunately, still wobbly.

Well, the hair cutting sort of went the same way. A little off the left, a little off the right, and then repeat the process. It was during this finishing touch that the fellow asked me how many haircuts I’d given. Not being one to lie, I confessed that this was my first one. There was a noticeable increase of tension in the laundry area.

I continued with the trimming. I think maybe his ears were not on straight. That’s the only reason I can give for why the haircut turned out looking so bad.

Frankly, I can’t remember too much about how the session ended; I just remember it wasn’t good. In fact, I decided that I was best to work the night shift until he left the station. I did catch a glimpse of him the next day. He was wearing a sweater with a hood that he was using to hide my handiwork. I don’t blame him.

I was keeping a pretty low profile so I’m not sure how it all worked out. I suspect that Red took pity on the fellow and did his best to repair the damage.

I didn’t come out of hiding until the fellow left the site for the last time a few weeks later.

I don’t do hair anymore!

Back to Index

No Days Off

I mentioned earlier that a full complement of radicians was seven to nine people. This number gave you enough radicians for three, two-person shifts a day and still allow you to have a couple of days off a week. Losing anyone can create problem. Losing Tom Billowich from CAM Four because he missed a boogie created a major problem because we were already short-handed at that time.

We then went through a period of several months where we worked seven days a week, week after week, without any days off. Not that there was much to do on your day off, but it’s tedious working day after day without any end in sight.

Pushing weather limits had its consequences as you can see with this C-46, CF-HEI, at CAM-F.

At one point, this tedium was matched by a long spell of bad weather where we couldn’t get any supplies airlifted into the station for 28 days. The food was beginning to run low and tempers were running high. While we didn’t get to the point of looking at each other as possible sources of protein, the main freezer got pretty empty. If it got much emptier, we’d have had to send the station Eskimos out on a hunt for food. No mail (particularly no letters from loved ones), no movies, and no booze made for a group of very grumpy people.

It’s not that they didn’t try to get in to us. Every now and then the weather would look promising, only to have it close in by the time the aircraft arrived overhead. It was incredibly frustrating for the people at the airstrip to hear the DC-3 trying to land but ultimately having to go back to FOX Main with our mail and movies.

There was dancing in the streets (a figure of speech only, as there were no streets) the day the plane was finally able to land. The very first thing we all wanted was our mail as this was the main connection to the rest of the world for most of us.

Back to Index

This is Santa Claus Calling

I was fortunate enough to have another way to stay connected with the outside world as well as relieve the boredom. As the only amateur radio (ham) operator on the station, I had the use of the station’s emergency radio equipment which was a Collins 431-B1, 1000-watt transmitter, and a Collins 75A4 receiver, along with a three-element beam antenna. All excellent equipment and a radio amateur’s dream rig, with the one exception being that the beam rotor usually froze up during the winter months. We always made sure it was pointing south when we shut down the radios.

My radio call sign while I was in the Arctic was VE8SK or phonetically as Victor Echo Eight Sierra Kilo. However, around Christmas time I’d go on the air as Victor Echo Eight Santa Claus and I’d have ham operators lined up a mile deep to let their children talk to Santa’s station in the north.

Whenever possible I’d use the radio equipment to allow personnel to talk to their families through the use of other ham radio operators who had a device known as a phone patch. The phone patch would allow them to connect my radio signal into the phone line. This way we could call a person’s spouse and allow them to talk for as long as atmospheric conditions allowed. The service was most appreciated.

Back to Index

A Woman’s Voice

Another service that was appreciated was when we patched our air/ground communications with an airline stewardess (as they were called back then) into the PA system.

Once a week, Scandinavian 935 from either Vancouver or Calgary, I’m not sure which, would pass overhead en route to Amsterdam. On more than one occasion, I’d ask the pilots if it might be possible to have a chat with a stewardess. The pilots knew that we were in the middle of nowhere, keeping an eye on their progress, so out of appreciation for our services, they usually complied.

I was able to accomplish this feat during one Christmas Day when most of the station personnel were indoors relaxing. I patched the stewardess’s voice through the PA system to all the modules and we had a very pleasant conversation for some ten minutes until I ran out of things to ask her.

The sound of a woman’s voice to a bunch of guys who have been away from civilization for too long is like music. We had a short but nice symphony that day.

Back to Index

Escape from the North

When it came time to go out on my first R & R leave at about the nine-month point, I declined as I knew that if I went out then, I’d never come back. The thought of another seven- or eight-month stint up in this wilderness was just too much to bear. So I elected to stay on for another three months and left after a year on the Line.

I had another problem before going south—my weight. When I arrived on the DEWLine some 12 months earlier, I weighed in at about 120 pounds, soaking wet. Due to the great food and sedentary lifestyle, I now weighed 150 pounds. A weight, by the way, that I wasn’t to see again until I was in my late sixties, and then only fleetingly!

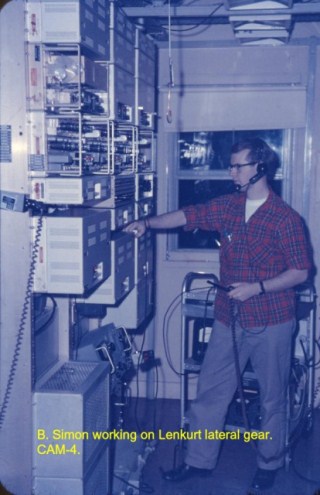

Here I am, wearing my imfamous, and always present, red shirt, taking meter reading on the VO-38 inter-site communications equipment.

Not only that, but my apparel had been reduced to one pair of pants and a red shirt that I loved with a passion. Every two weeks, whether they needed it or not, I’d run them through the washer and dryer. I’d sit in the laundry area in my underwear, reading a book, until they were done.

My beloved shirt had a number of rips and tears which I had repaired with masking tape. I had to use masing tape as duct hadn’t yet been invented as yet. I’d put the masking tape on the inside so it didn’t show. All in all, this was not the best clothing to go south in, so I measured myself up, found the Sears catalogue, and ordered a three-piece suit for the princely sum of $29.99, including a second pair of pants. Of course, I also bought a couple of shirts and a pair of shoes as well. Now I had my “going-to-town” clothes and was ready to tackle the south. Frankly, I don’t think I looked particularly dapper, but it was the best I could do under the circumstances.

Back to Index

Not Much Pay

The company had an arrangement to send your pay directly to the bank; however, you could have them send you a cheque every two weeks so that you had some spending money. I elected to have a dollar a day sent up, so every two weeks I’d get a company cheque for 14 dollars.

There are not a whole lot of things to buy on the DEWLine. I didn’t drink beer, so I sold my beer allotment to the highest bidder, and I didn’t know how to gamble, so when I went south on R & R, I had 26, 14-dollar cheques to cash.

The teller at the bank was curious about the fairly large number of small domination cheques. When I told her that these were my paycheques, she sadly commented that I didn’t get paid much. If she only knew!

Back to Index

Being Bushy

It took a while to get acclimatized to the hurley-burley of civilization again. Basically, I was in a condition we called “bushy,” or out-of-touch. If I was in a room with more than five or six people, I’d begin to feel claustrophobic and have to get out. If I wanted to get to the other side of the street, I’d simply strike out across the road, totally oblivious to the traffic. More than once I almost got knocked into the next life. It’s an odd feeling of being disconnected with the here and now.

One of the highlights of my vacation was a trip to Chicago to visit the Museum of Science and Technology, where I was able to wander through the World War II German submarine

U-505 and watch the move of its capture during the war. It was a great place to visit if you were technically or scientifically minded. I also checked out the Cleveland School of Electronics which had a pretty comprehensive correspondence course on advanced electronics. I signed myself up for the course and used it to educate myself further, as well as pass the time on the Line.

If the museum was one of the highlights of the vacation, an incident with my mother was a definite low point. It probably comes as no surprise, but when a bunch of guys are forced to live together in close quarters for prolonged periods of time, their language can go to pot, to put it politely. As I recall, on the Line, about every fifth word out of a person’s mouth was the famous “f” word. I mean, it got to the point that you didn’t even realize you were saying the word, it just came out.

So you can imagine my mother’s horror when, at breakfast one morning, I asked her to pass the f**king butter. She hauled off and hit me across the face. Stunned, I asked why she’d hit me. When she said, “Don’t use that kind of language with your Mother,” I asked, “What f**king language?” She hit me again. I instantly figured it out and I quickly learned to be a lot more careful about what came out of my mouth while I was down south.

Apart from insulting my Mother, I managed to survive my R&R and returned to the DEWLine, this time via Winnipeg as TransAir had won the contract and had replaced Nordair on the North/South trips. I was all refreshed and ready to complete the last few months of my first contract.

Back to Index

Returning North

The flight from Winnipeg to Hall Beach was somewhere around 12 hours. Twelve boring hours. In an attempt to minimize the pain of the trip, someone suggested that it would be a good idea to get drunk before climbing on the aircraft and thus sleep for the majority of the trip. It sounded like a pretty good idea (at the time), so I bought a 16-ouncer of rye and promptly got stupid drunk.

I don’t remember getting onto the plane, but I do remember waking up a couple of hours into the flight and being deathly ill for the remaining ten hours of the trip. At one point, I had apparently gone into the lavatory to throw up and managed to get on my knees in front of the toilet where I promptly fell asleep again. Once they figured out that I was missing, the stewardess, as they were referred to back then, tried to open the lavatory door only to find that I had inadvertently jammed it shut. They were able to open it enough to reach in and grab the scruff of my neck and lift me vertically enough to open the door and get me out and back to my seat again.

I didn’t attempt that trick ever again.

Back to Index

Time to Move On

I had been at CAM Four for over a year at this point, so when I returned from my R & R it was time to move along to a new adventure.

Being a radician on one of the Intermediate Sites (I-site) was not a desirable position. First off, it was a lonely existence as the station had a normal personnel complement of only three to five people: a station chief, the radician, a mechanic, a cook, and a couple of Eskimo workers. Sometimes either the radician or the mechanic held the position of station chief. As you were the only technical person on the station, you couldn’t really leave the building too far or for any length of time as you had to be available 24 hours a day to deal with any equipment failures.

I’m not sure how I got sucked into going to CAM D (Simpson Lake) which was located between CAM Three and Four. I think it was the promise of being considered for a position on the Sector Crew after I served a term at the I-site. The Sector Crew was a group of semi-elite technical people who travelled from station to station across the sector, solving problems that the site personnel couldn’t solve or providing additional assistance as needed.

CAM-D and its 300 foot tower with the main building underneath. Actually, that’s the whole station right there.

However it came about, I found myself at this tiny station, truly in the middle of nowhere. Its most prominent feature was its 300-foot tower that held the Doppler antennas that pointed west toward CAM Three and east toward CAM Four. It stuck up like a sore thumb on a frozen cadaver.

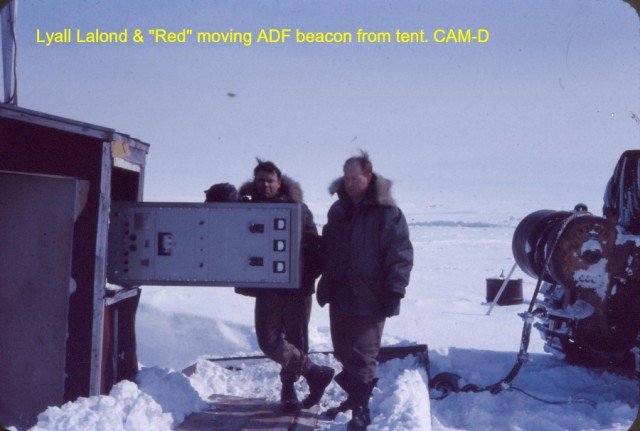

As you drove up to the main building from the airstrip, you passed the two Eskimo houses and the original Jamesway huts that were used by the construction crews during the building of the station. One of the huts still held the radio beacon that I was ultimately to move to the main building.

The I-site’s main building made the Aux-site look like a palace. It was constructed of five of the 25- by 16-foot modules, side by side in a mini-module train, all mounted above the frozen tundra on four- to five-foot stilts or pilings.

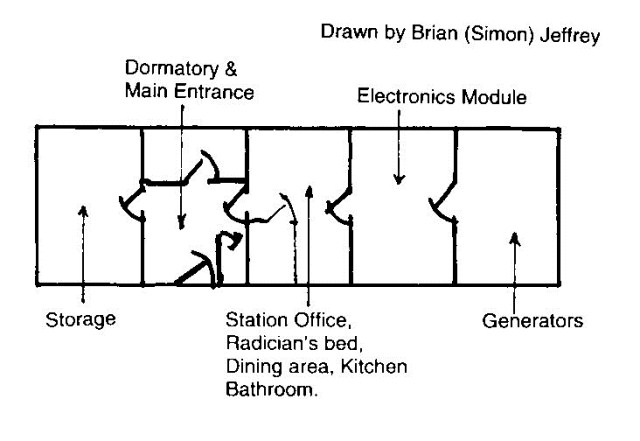

As before, my memory is hazy on the layout of the building, but I found some information in an article by Martin Allinson, who spent far too much time on I-sites in Dye Sector in the early 1960s. The following is his description of the building layout:

- Module 1: Generator Room containing two 40 KW diesel generators.

- Module 2: Electronics Module containing the four Doppler radar transmitters.

- Module 3: Station office, Radician’s bed, Dining area, Kitchen, Bathroom

- Module 4: Dormitory and main entrance door

- Module 5: Storeroom

The building was entered through the main door in Module 4. There was a small corridor about 12 feet long that joined into the main passageway that ran through the whole length of the building.

Module 5, which was to the left as you entered the main passageway, was devoted to storage for food, spare clothing, and so on, and a large water tank.

Turning to the right at the main passageway, you had a cage that contained the 60 Hz motor, 400 Hz generator sets and a big sewage tank on the right and the dormitory on the left. The dormitory contained three double bunks and was the sleeping area for the mechanic, cook, and any winter visitors, such as members of the sector crew.

You entered the “living module” (Module 3) through a fire door. On the right, up a few steps, was the bathroom and shower. This took up one quarter of the module. The other quarter on the right was the kitchen area with a water heater, stove, sink, cook’s table and a washing machine for doing your laundry.

On the left of this module were the station chief’s bed and his desk, the dining table, and the radician’s bed (with the radar equipment alarm by his pillow).

Module 2, the electronics module, contained the four radar transmitters to the left and the radician’s workbench, storage shelves, desk/communications centre to the right.

Module 5 held the two 20 KW diesel generators, but thanks to good soundproofing, the noise level wasn’t excessive.

CAM-D module train taken from part way up the 300 foot tower. The generator module is on the left. The building at the top right was the garage.

What I’ve described here was the layout for CAM D. On some of the other I-sites, the entrance door was on the other side of Module 4.

I can’t remember the name of the radician I replaced at CAM D, apart from the fact that he disappeared on the next available aircraft after familiarizing me with the four FPS-23 transmitters, the AN/FPT-4’s, the electrical power switching panel, and the Gonset Air/Ground radio.

Back to Index

Working Around the Clock

I arrived just in time to partake of the annual resupply airlift. This is when all the POL (Petroleum, Oil and Lubricants) supplies for the whole year are brought to the station. I don’t know how many hundreds of 50-gallon drums of diesel fuel we received for the generators, but they all had to come by aircraft. They usually used the venerable C-46 Curtiss-Wright Commando aircraft. The C-46 probably had about three times the cargo capacity of the Douglas C-47 (also known as the DC-3) which normally flew the route year round.

Even with three times the payload, it took almost two weeks of continuous flights to resupply the station. The aircraft flew 24 hours a day, and while they had extra pilots for the aircraft, we were on our own. I literally slept at my desk by the air/ground radio in the electronics module. I would be awoken every couple of hours with the arrival of another plane. Only bad weather gave us any break from the endless grind. (At one point they flew in one of the new radicians, Bruce McLean, to help out with the air/ground duties which gave me some respite.)

The rest of the station crew, with usually included a few extra people for the summer, had to unload the barrels from the aircraft, and drive them to the main site where they unloaded and stored them. Then they repeated the process over and over again as each aircraft arrived.

Back to Index

Lesson Learned

Bill Wands, an electrician and genuinely nice person, was the station chief when I first got to CAM D. Bill assisted me in removing our radio beacon transmitter from one of the Jamesway hut/tents and moving it up to the main building where we had to install it in the electronic module.

“Dusty” Lyall Lalonde (Sector mechanic) and “Red” removing the radio beacon from the airport ‘terminal’ building and onto a sled for relocation to the main module train.

We had to dig down into the tent to get at the door in order to remove the transmitter. We then laid it on a sled and dragged it to the main building with a bulldozer. Once the transmitter was installed in the electronics module, I had to climb the 300-foot tower to connect one end of the new antenna to the top of the tower.

By the time I managed to climb the 30 storeys to the top, my legs were like rubber. As I reached over the edge of the tower to connect the wire using a nut and bolt, the nut slipped out of my hand and fell 300 feet to the ground. I suspect it continued going 300 feet into the ground!

Stupidly, I had only brought one nut and bolt with me. Now all I had was a nutless bolt. There was nothing to do but climb down the tower, grab a handful of nuts and bolts, and climb the tower again.

By the end of the second 300-foot climb, even my leg muscles had muscles and they were screaming in agony. I learned a valuable lesson that day and always made sure I carried spares of everything I could whenever I had to do stuff like that again.

Back to Index

Doctor Brian

Being the only radician on an I-site meant that you were also the first-aid person as well.

The Eskimos at CAM D lived about a half-mile away, halfway between the airstrip and the few modules that made up the station. One of the Eskimo women was with child, pregnant so to speak, and was growing subtly larger with every passing month. As she usually stayed in the Eskimo quarters, she was generally out-of-sight and out-of-mind. She became top-of-mind one evening when her husband brought her to the main building complaining of stomach cramps. Stomach cramps? How about labour pains? First-aid training notwithstanding, I was not prepared for this!

What to do? The first challenge was communication. The Eskimo, whose name I’ve long forgotten, didn’t speak very good English and I sure as hell didn’t speak Eskimo. No one seemed to know just how long the lady had been pregnant or when, exactly, she was due to give birth.

I immediately rummaged around our limited library and found what I was looking for, the St John’s Ambulance First Aid Manual. I opened it to the index and looked for “emergency childbirth.” There it was. I was saved. I quickly opened it to the emergency childbirth section and here’s what it said:

1. Make patient comfortable.

2. Call a doctor.

Yikes! This I didn’t need. The closest doctor was in FOX Main. I immediately got on the horn to CAM Four and had them patch me through to FOX Main, where I tried to locate the doctor. Time stretched on forever as I waited for my saviour to call. Finally…a call from CAM Four. They had the doctor and were patching him through to me. He asked me how far along she was. I told him I didn’t know. He asked if she was dilated. I didn’t know. Hell, I was only 21 and had never really looked at these things before!

He finally gave his advice. If it was a boy, I should tie the umbilical cord with a blue ribbon and if it was a girl I was to tie it with a pink one. I went ballistic.

I told the doctor, in no uncertain terms, that they were to send a plane, now, either to take her or me out of here. I didn’t mind changing klystrons but I hadn’t signed up to deliver babies.

After I calmed down, they agreed to send a plane, and eight hours later my Eskimo friend was on her way to FOX Main and competent medical help. I’m sure that both of us were breathing a lot easier.

It turns out that she really did only have stomach cramps and gave birth to a healthy baby girl about three weeks after her evacuation from CAM D.

Back to Index

The Dancing Washing Machine

It was a big day at CAM D. We received a new washing machine to replace the one that had died several weeks before.

Now, washing machines were no big deal, unless you were without one for several weeks. By this time, some of our clothes weren’t just standing up by themselves; they were walking around looking for some fresh air and begging to be washed.

We got the thing off the plane and into the back of the 4 x 4 for the one-mile trip to the main site. The Eskimos wanted the packing case for something so they quickly spirited the material away, never to be seen again, leaving us to manhandle the heavy, commercial-grade unit, into the building.

Our famous “dancing washing machine” can be seen on the left foreground. Rene Cote was the station chef.

We squeezed the unit through the doorways and into the kitchen/eating area module where we placed it approximately where the old machine had been. We were all anxious to give it its first workout. While the cook prepared the final touches to supper, we put in our first load. A really big load.

It was while we were all eating around the small table that the trouble started. All of a sudden, the machine went into its high-speed spin cycle and took off, dancing and hopping around the room. The imbalance of the wet clothes in the drum had turned this normally docile machine into a mechanical bucking bronco. After the initial surprise wore off, three of us jumped on top of the machine to try and contain it before it did too much physical damage to the facilities.

There we were, all three of us, hanging on for dear life as this killer washer tried to buck us off and trample us. It just kept on dancing and bucking for what seemed forever until it finally moved far enough that the power cord came free from the wall outlet and the machine, thankfully, calmed down.

As we surveyed the damage, we realized why we had put the machine approximately where the old machine had been and not exactly where it had been. There were concrete blocks in the way. In our zeal for clean clothes, we had forgotten that the old machine had been mounted on these blocks. Now we knew what the blocks were for. They weren’t to just raise the machine off the floor as we had thought; they were to keep the machine from dancing away with our clothes.

No one said much as we unloaded the machine, mounted it on the concrete blocks, and went back to finish a cold supper with the new washer humming gently in the background.

Back to Index

King of the Northwest Mounted Police

It was like a scene from a bad movie. There I was, not knowing what to do when King of the Northwest Mounted Police, in the form of an RCMP constable, showed up at the door and saved the day.

It started earlier that evening. As I mentioned before, as the only radician at CAM D, I doubled, hesitantly, as the first-aid person. One of the Eskimos brought his four-year old daughter up to the main modules with a crushed finger. Apparently, little Emily had gotten her finger caught in a door and basically squeezed it enough that it had broken open at the top.

Albeit small, it was a pretty nasty-looking wound. In cleaner southern climes, it might not have been too much of a problem; however, having seen the Eskimo quarters, I was afraid of Emily getting an infection and losing her finger or perhaps her hand.

According to the station’s St John’s Ambulance First Aid Manual, I was to give her a shot of penicillin. OK, but where? I had three ampoules of penicillin and a needle, but no instruction as to where to inject it.

I’d always gotten my penicillin shots in the butt. However, as I was never watching when it happened, I wasn’t sure exactly where in the butt to stick it. This is when King of the North arrives on the scene.

Now picture this. I’m located about 120 miles above the Arctic Circle, some 50 to 70 miles from the nearest Auxiliary site, and 250 miles from a doctor who wasn’t available anyway, when there’s a banging on the module’s main door. In walks this RCMP constable who had just parked his dog team—yes, a dog team—in front of our building, and he wants to know if he can bed down for the night with us. Is this out of Hollywood, or what?

I welcomed him with open arms because I knew that RCMP personnel have extensive medical and first-aid training. I quickly explained my mini-medical emergency to him and he took charge. He gave the shot to Emily, bandaged her finger, and calmed her down.

Another life saved in the nick of time by King of the North.

I was to have other medical adventures with Emily over time, including helping her with a bout of impetigo, which is a rash that can be quite uncomfortable. Emily’s mother and father were Margaret and Peter Nakoolak and I came across them a number of times as I travelled around this part of the Arctic.

Postscript: As a footnote to history, in 2007 someone saw the picture of Emily that I had posted on my personal website and I received an email from Emily’s sister, also called Emily. Apparently, the Emily I had known had died sometime after I left the Line and this lady had been named Emily as well. Emily #2 had never seen a picture of her sister. She told me that both her parents, Peter and Margaret, were still alive and living in Nunavut which is the new name for the Northwest Territories.

Back to Index

No Rest for the Wicked

Intermediate sites were situated between two Auxiliary sites and transmitted signals east and west which were picked up at the Aux-sites. It was a Doppler system and was intended to fill the gaps between stations. In fact, it was called a Gap Filler System. The theory was that should an enemy aircraft try to sneak between the two Aux stations, the transmitted signal would be disturbed and an alarm would go off at the console at the relevant Aux station.

Theory is one thing and practice is another. Any number of things would cause a false alarm. One of those many things was a noisy transmitter at the I-site, so it was not uncommon to get a call from one or both of the Aux-sites at any time of the day or night to go check the FPT-4 transmitters.

Here I’m checking the AN/FTP-4 transmitter, probably in the dead of night. Note the ever present red shirt.

If the call happened to come in the middle of the night, you had to get up and go tend to the electronic beasts in the electronic module. This usually meant switching over to the standby transmitter and then tending to its errant brother.

Because the radician shared the sleeping and living module with others, if you were up all night, the only place you could sleep during the day without being disturbed was in the midst of the electronic gear. At least it was toasty warm in the electronics module and the drone of the diesel generators in the next module helped put you to sleep.

The whole gap filler radar system was from an earlier era and fraught with false alarms to the point that many of the console operators would simply ignore the alarm or turn off the console displays altogether. They finally turned off the system for the last time and closed down the I-sites in 1963.

Back to Index

Now That’s Cold!

I’ve been outside in minus 50-degree weather in a shirt. Not for long, mind you, but I wanted to see what it was like. Frankly, it was cold! Interestingly enough, it didn’t feel cold until the wind hit you, then you felt the cold deep inside. It felt as if someone had slashed you with a razor. It was an odd feeling.

It was at CAM D where I did my first scientific experiment: the famous disappearing water act. There is a temperature at which, if you throw warm water into the air, it virtually disappears. I’ll admit I didn’t start out to do a scientific experiment; it just turned out that way.

I was in the electronics module one evening and the rest of the crew were in the living module watching a movie when I had the urge to urinate. As usual, the movie screen was set up against the door to the electronics module. As I didn’t want to disturb the gang just because I had to take a whiz, I went through the generator module and stepped outside into the minus 50 degree weather and quickly relieved myself.

When I went outside the next morning there was no evidence of my having relieved myself. The urine had simply evaporated into thin air. Now that’s cold!

Another small step for mankind.

Back to Index

A Time Management Lesson

Our station chief, Bill Wands, was whisked away one day and replaced by Ray Dawes. Ray was to teach me a lesson that I still use to this day.

Ray was a mechanic. He was a big man with a gentle disposition, who didn’t much care for the paperwork involved in the job. With every lateral flight came a ton of paper that had to be dealt with. I’d watch Ray wade through the piles, reading this, noting that, and throwing away a fair amount of the stuff, as well.

One day, while watching Ray sifting through the crap, I noticed that one of the messages he threw away was a message from his boss requesting him to do something or other. I asked Ray why he threw it away. He replied, “If it is really important, they’ll send it again!”

Interesting philosophy! Ray would mentally log in the first request and would only take action after he received a second request. What a time-and work-saving technique! Apparently, it worked well because Ray never got into trouble and went on to be the station chief at the FOX Three Aux-site where he did an excellent job.

Over the years, I’ve been able to use Ray’s “Wait until the send it again” technique to good use.

Back to Index

Time to Move Along Again

My contract had come to an end and it was time to leave CAM D and go out for my EOC (End of Contract) leave. My first contract was up in November 1961. Fortunately, or unfortunately, we were short-handed, so when I offered to delay my EOC leave, it was well received and I stayed on for several more weeks, working over the 1961 Christmas period, before returning to civilization again. As a reward for my “generosity” of helping out during the Christmas period, I was allowed six weeks rather than the normal four weeks for my EOC leave.

By now I had some decent going-to-town clothes and I was much more careful with what came out of my mouth as far as swearing was concerned. As such, I had a pretty good holiday, with the exception of disappointing my mother yet one more time.

Like most moms, mine had kept my bedroom ready for my ultimate return (the return of the prodigal son). When I told her that I had rented an apartment for the six weeks so that I could be on my own, she wasn’t a happy camper. I didn’t mention to her that I had high hopes of running a den of iniquity. She was crushed that her only son didn’t want to spend his hard-earned holiday sitting with his mother. While she ultimately got over it, I don’t think she every truly forgave me for my heartlessness.

One of the additional problems of being the only (and therefore favourite) son of a proud Mother is that she was forever offering my technical services to her friends. Your radio doesn’t work? No problem, my son will fix it for you. Broken toaster? Bring it over for Brian to fix. Television on the fritz? Brian will take care of it.

I didn’t want to spend my vacation time repairing people’s rejects, so I finally had to tell her that I didn’t repair TVs, radios, or toasters anymore, and that if her friends had any radar sets or high-powered transmitters that needed looking at, I’d be delighted to help out. She wasn’t too pleased. She thought I had a bad attitude. Mothers!

In all fairness, my mother was a wonderful person who always believed in me and felt that I was a genius when it came to electronic stuff. I was about 15 or 16 before I came to the realization that I wasn’t a genius (damn!) but just a guy who was handy with his hands and who had an affinity for electronics.

Back to Index

Here We Go Again

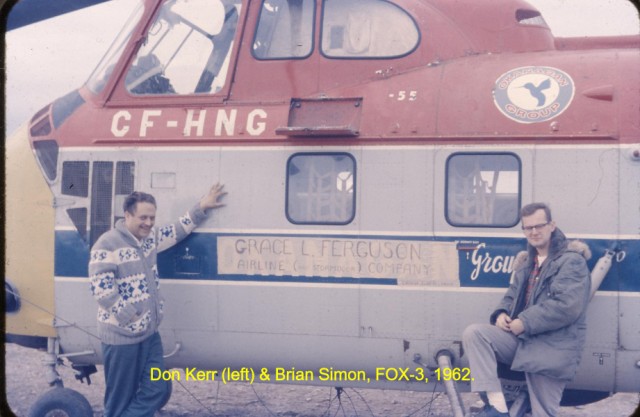

Upon my return to the Line, I got the position on the sector crew that I had been promised. Because of my technical background, I was assigned to look after the air/ground equipment on the sector’s six stations.

Being a sector radician was a bit of a lonely existence. For the most, part you were an outsider upon arrival at a station and treated as such. As an introvert, I wasn’t bothered too much by this. Once you were there a time or two and demonstrated that you were more of a help than a hindrance, you were adopted by the station, or at least tolerated by them.

I did manage to make a spectacle of myself during a first visit to one of the sites. I had just come from a site that had a terrible chef. Not only was the food badly cooked, it was always cold or lukewarm at best. I was to the point where I’d just pop whatever it was into my mouth and swallow it as soon as possible.

So imagine my surprise when I sat down for supper at the new site and popped a searing hot chunk of potato into my mouth. I severely burned my tongue and the roof of my mouth before, to everyone’s horror, I spit the thing back onto my plate and jumped up. I’m not sure but I think I might have used the “f” word a time or two. What a wonderful first impression I must have made.

As sector crew, you had to travel with all your worldly possessions which you would throw on the plane moments before you got thrown on along with the sacks of the all-important mail and the movies. In the overall scheme of things, the movies and mail rated more highly than the sector crew did.

Back to Index

Movie Time

After being shown at the Main station, movies were always sent to the most westerly station in the sector and would work their way across the sector from west to east. If I was travelling from station to station, east to west, I’d end up missing every second batch of movies. On the other hand, when I was travelling from west to east, I’d get thrown on the plane along with the movies, and both the movies and I would be off-loaded at the next station. This meant that I’d get to see the same movie for several weeks in a row. Not many of the movies were worth seeing more than once, but when you’re desperate you’ll watch almost anything.

Back to Index

God’s Will

Because I got the opportunity to work on the same air/ground equipment at every station, I got to know the technical idiosyncrasies of the various pieces of gear. One such idiosyncrasy almost got me in hot water with one of the company field inspectors from the head office in Paramus, NJ.

These inspectors would arrive on your doorstep from the south and follow you around to ensure that procedures were being followed and that the work was being done properly. They tended to leave you alone for the most part, but every now and then you’d get an eager beaver who knew it all even though they knew very little. (I was tempted to say they knew nothing but that would be unkind.)

The Collins VHF receivers that I worked on had a particular bias measurement that simply never met the specifications that were outlined in the preventative maintenance schedules. After checking and rechecking all 36 receivers in the sector, I kept getting the low reading. The maintenance schedule called for a value of at least -5 VDC at a particular test point and I could never get anything better than about -4.5 or so.

One day I was being shadowed by a HQ inspector who was watching my every move. When I got to this particular test point, I noted the low value and was about to move on when he stopped me and asked what I intended to do about the low reading. I showed him that the other two receivers on the station also measured low and that I’d found the same low value all across the sector. He was a bit confounded by this phenomenon and wondered what we should do about it. Having already tried every technical trick I knew, I had come to the conclusion that the specifications were in error and not the receivers. He didn’t seem too keen on accepting that explanation, so out of frustration, I said, “Maybe God wants it that way.” Of course, I was just kidding, but little did I know that this gentleman was extremely religious and took my comment quite seriously. He furrowed his brow and pondered the comment for a moment or two and then made the observation, “Maybe you’re right.” Problem solved, subject closed. Or so I thought.

Unfortunately, it didn’t solve my problem because the inspector assumed, incorrectly, that I was a potential “believer” and he wanted to pursue the saving of my soul. I didn’t catch on to this for a while because, being young and curious, I was interested in religion, and in the beginning I was comfortable chatting about the subject. I got increasingly more uncomfortable as the fellow increased the pressure on me to go to a quiet part of the station and “kneel with him in prayer.”

At this point I began to realize that the situation was getting out of hand and I tried to wind down the topic without much success. He was due to move along to another station when a bizarre event occurred.

I rejoiced when he took off for the airstrip. I was free, or so I thought! Strangely enough, the aircraft ran into mechanical problems and had to return to the station. He immediately sought me out and told me that God had brought him back to the station for a particular reason and it became quite clear that I was that reason. Having no idea how to cope with the situation, I started working the overnight shift and hiding out in order to get away from the fellow.

He finally had to go on with his mission, both technical and religious, and I learned to be a whole lot more careful when discussing religion and politics.

Back to Index

The BOPSR Club

As a member of the sector crew, I didn’t really have a place to call home. The members of the sector crew were usually constantly on the move, going from one station to another across the sector, looking after their assigned group of equipment. As mentioned, we were usually thrown on the plane right after the movies and mail and got off the plane immediately after them.

If we had a home, it was the BOPSR Club at FOX Main. Named after one of the many reports (Building & Outside Plant Status Report), the BOPSR Club was a single leftover module that sat, all by itself, about 200 feet from the main module trains. It had electricity, a space heater, some eight to ten bunks, and that’s about it. Oh, it had one other thing. It had a urinal of sorts, but more about that later.

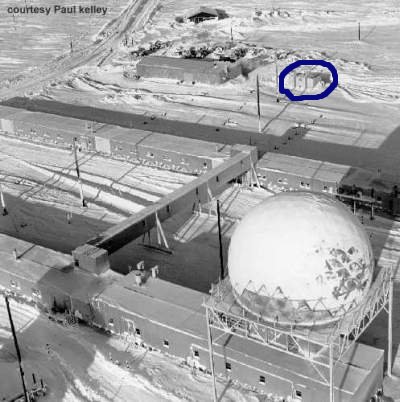

BOPSR Club (circled) at FOX-Main. Home of the Sector Crew when they passed through FOX Main. Photo by Waly Getman, taken from the FPS-23 tower.

Whenever members of the sector crew were in FOX Main, they stayed in the BOPSR Club. As it was rare for the whole crew to be at FOX Main at the same time, the bunks were often used by personnel coming up from the south while they waited lateral transportation to their assigned sites.

Newcomers to the Line who stayed in these less-than-posh quarters were easy prey to the old-timers who, in exchange for the newcomer’s booze, would spin tales of life in the north.

Back to the urinal. As the module had no washroom facilities and as it was a long, cold, 200-foot walk to the main building, some enterprising soul had built an enclosed veranda-like addition through which he stuck a metal funnel so the men could relieve themselves without freezing anything. The funnel had a hose that ran to a 50-gallon drum. This wasn’t a problem in the winter when everything froze very quickly, but in the summer months when this drum thawed out, we all stayed on the road and away from the club. Not a pleasant aroma for a while.

It was the winter of 1962. I and a couple of other sector crew members were between trips and hiding out in the BOPSER Club when we were blessed with a couple of newbies fresh up from the south and bearing gifts (booze).

I rarely drink unless it’s there and if it’s there I drink. It was there and I drank. Every now and then, one of us would get up and go use the urinal in order to make more room for the booze. I don’t know about you, but the more I drink, the drunker I get and the drunker I get, the sleepier I get.

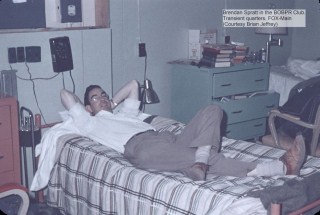

New Radician Brendan Spratt inside the BOPSR Club awaiting assingment. Nore that neatness doesn’t count.

On one of my trips to the urinal, I fell asleep standing up, and a part of my body, which will remain nameless, but which rhymes with the planet Venus, came in contact with the metal funnel. Anyone who was a kid, particularly of the male variety, knows that when a part of your body, your tongue for instance, comes in contact with frozen metal, you stick to it. That’s what happened to me.

I awoke instantly to find myself attached to the funnel by my penis! What to do? I tried spitting to see if the warm saliva would free me from my bounds. No luck. Finally, I did what every young child does when they find their tongue stuck to the metal fence or pole, I pulled away, leaving a small part of me still attached to the metal funnel.

Fortunately, alcohol has an anaesthetic property that helped dull the pain. I’ve always claimed that, had this accident not happened, I would have been a danger to all womankind (don’t I wish).

Back to Index

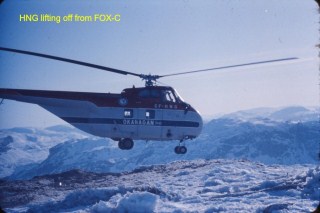

Another Kind of Freezing

I had yet another adventure with the cold that I didn’t care much for. I was on a flight from FOX Three (Dewar Lakes) to FOX Main when the heater in the DC-3 decided to quit. These heaters were cranky at the best of times and this was not one of the best of times. The outside temperature was in the order of minus 40 or minus 50 degrees Fahrenheit and the temperature inside the aircraft quickly began to drop to match those numbers.